Unless you’ve been glued to the TV watching Monk marathons the past week, you heard that Mark McGwire, once the greatest show in baseball, finally made it official: he cheated.

McGwire’s admission to using steroids throughout the 1990s couldn’t have been much of a surprise to anyone, although it was strange he claimed to have kept it a secret from his closest friends and family. (Psst, Mark…I think they knew.)

Almost five years after his infamous “I’m not here to talk about the past” routine at the 2005 congressional hearings, McGwire was granted yet another forum to give us the juice on the juice, to finally bring the fans into the closet of one of the Steroid Era’s greatest violators. Before his interview with Bob Costas on the MLB Network, I was on the edge of my seat waiting to hear it straight up from one of the good guys of the game.

Then, just like 2005, he blew it again. This was Mark McGwire: Crash and Burn II.

What an opportunity this was supposed to be. To pick the brain of an admitted steroid user who had such a huge impact on baseball’s record book was unprecedented. Costas tossed McGwire several lob balls trying to get him to explain how much his use of steroids had to do with any increases in his size, strength, numbers, or the distance of his homers. You could see Bob begging for Big Mac to take a rip.

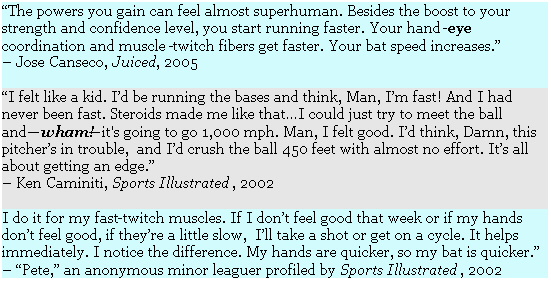

Nothing. McGwire left the bat on his shoulder, killing the entire investigative process before it ever got to first base. He downplayed the role of steroids on his game, saying he used “very, very low dosages,” and insisted he could have done the same damage with his bat—such as the 70 homers and the cluster of 530-foot bombs—with or without steroids.

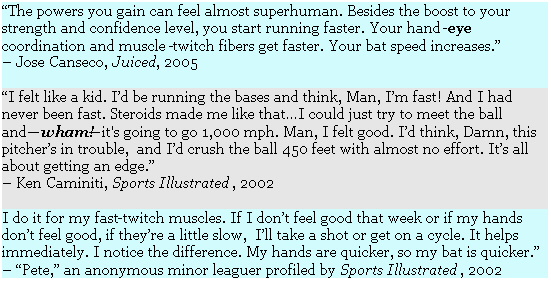

In commenting on Big Mac’s confession, Howard Bryant said that “being able to move forward is only possible when the past is confronted.” That’s cool in theory, if we could actually learn something from that past…such as with these types of confessions:

Big Mac? He told us “there’s not a pill or an injection that’s gonna get me the hand-eye or give any athlete the hand-eye coordination to hit a baseball.” I respect his courage for coming forth about his steroid use to the nation. But how could he really believe what he’s saying here? Is he just keeping his cards close to his vest?

It was almost a year ago that Alex Rodriguez left us hanging as well. In his own admission, A-Rod said he wasn’t sure how he benefited from using steroids—after telling us he injected himself for three years.

There’s a reason for those first two letters in the word “PEDs,” right? The only way this starts to make sense is that their sense of pride—which McGwire and A-Rod have enough of to fill an entire ballpark—somehow creates some form of denial in their own minds as to how they think they achieved what they did. Deep down, they don’t want their fans to think even for a millisecond that their virtuoso performances came from a chem lab.

This is hugely disappointing for those hoping to one day get the record straight on baseball’s Steroid Era legacy before it disappears into an abyss of uncertainty. If players continue to take the same stance as McGwire and Rodriguez, the fog of the 1990s may never clear up.

In lieu of Big Mac slipping us any meaningful nuggets about his steroid use on his way to the Cardinals training camp next month, the next best thing is to remind ourselves of the story of how Big Mac became a legend. Sometimes there’s enough detail to finish out most of the puzzle and get a really good picture of what went on, even with a few pieces missing.

So I give you an excerpt from my soon-to-be-released book Stealing Greatness. Here is “Mark McGwire’s Jacuzzi Moment.”

***

“I rededicated myself to baseball.”

—28-year-old Mark McGwire, October 1991, still digesting the throes of his worst season

With those words, Mark McGwire resolved to do something about a career that was slipping away. The revelational moment came for him while sitting in a Las Vegas casino Jacuzzi after the 1991 season. It was October, and Mark was bummed about watching the baseball playoffs on television for the first time in four years. After three consecutive World Series appearances, his dynastic Oakland A’s fell through a trap door and landed in fourth place. But that wasn’t the worst part for McGwire. The A’s empire was starting to crumble, and Big Mac was a big reason why.

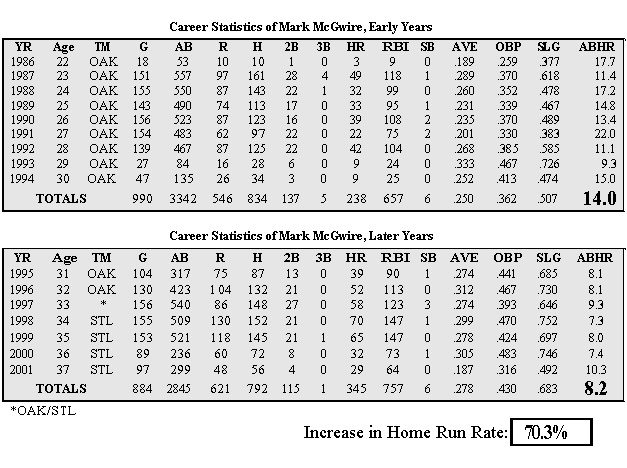

After finishing that season with a pitiful .201 batting average and a career-low 22 home runs, McGwire had never felt so inept at hitting a baseball. In fact, his hitting woes stretched all the way back to May of 1989. McGwire hit just .220 over almost three seasons. His career had officially reached chronic-alert status.

Slumps in baseball are like colds. Every player gets them from time to time, and they usually last several days to a few weeks. Once in a while, even the best players hit a funk for a month or two. But there is no such thing as a three-year slump. If a player performs at a certain level for that length of time, then that is his normal playing level. According to those who have studied statistical analysis, slumps and hot streaks are mere illusions of numbers bunching together according to the baseball winds of fate; it all eventually evens out to what they are meant to be. At that point in time, Mark McGwire was truly a .220 hitter.

Although he was at the lowest point he could possibly be without losing his place as a starter, McGwire did have a few things going for him. He was still on the young side, having just turned 28. He hit at least 30 homers in his first four seasons, becoming the first player to ever do so. Then there was that supernova rookie season in ’87 that let everyone know what the big guy was capable of doing in the majors. That year, McGwire exploded into the baseball world at 23 years old by slamming a rookie-record 49 home runs while knocking in 118 runs and batting .289. And as if to foreshadow what was yet to come, McGwire’s 33 home runs in his first 79 games that year stirred up talk of Roger Maris and the single-season home run record of 61 for the first of many times in his career. But like so many Maris chasers before him, McGwire slowed during the second half, making the chase a non-issue by Labor Day.

Let’s put some perspective on McGwire’s phenomenal rookie season. With 1987 regarded as one of the greatest home run “spike” seasons ever, McGwire had plenty of company posting an exorbitant home run number. Whether due to an exceptionally-juiced baseball or unusual weather patterns, the impact on the home run was felt across the league, with many players beating their next highest career home run totals by at least 25%, such as Wade Boggs (24/11), Andre Dawson (49/32), and George Bell (47/31).

There was one other omen from 1987: Mac was already pumping the iron. “Six days a week in the off-season, I lift weights,” McGwire admitted that year.

McGwire’s numbers came back to earth his second season with 32 home runs, 99 RBIs, and a .260 batting average. It was good enough to co-lead the A’s, with Jose Canseco and Dave Stewart, to the World Series for the first time in 14 years, where they lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers and a limping Kirk Gibson. The Oakland enterprise was starting to roll, and McGwire’s potential was still sky high.

Enter the three-year slide. From 1989 through 1991, McGwire batted .231, .235, and .201. The A’s won it all in 1989, and would make it back to the World Series in 1990. But by ’91, Oakland’s ship was sinking, and Big Mac’s once-voluminous flame was flickering like a candle in a gusty wind.

While sitting in that Jacuzzi and watching the Minnesota Twins and Atlanta Braves battle for the 1991 championship, McGwire suddenly realized what it meant to be in the World Series, and how quickly opportunities like that can dry up. He said that watching those games got him “pumped up,” waking a spirit within. He realized he had to do something about the direction his career was going, to control his own destiny.

Cue in the Rocky music. That winter McGwire hit the weights like a man possessed. By most accounts, he gained an additional 20 to 25 pounds of muscle within a surprisingly short period of time. And to inject a little nasty-boy persona into his nice-guy image, McGwire unveiled his goatee for the first time in his career, which made him bear a slight resemblance to heavy-metal rocker James Hetfield, lead singer for Metallica. The next year, Big Mac’s bat started jamming like Kirk Hammett’s guitar—loud and with plenty of punch.

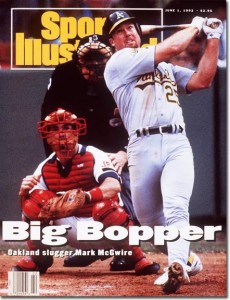

Sports Illustrated, June 1992

The 1992 season couldn’t have started better. New hitting coach Doug Rader brought a philosophy to the A’s that was very Mac-compatible. With some new adjustments at the plate, McGwire had a swing without hitches and was now lightning quick. And what better way to announce his resurgence then to invite the ghost of Roger Maris back to the party? With a .313 batting average and 17 home runs in his first 38 games, McGwire restored his place as a premier power threat, and was once again on a Maris pace. But just like in ’87, the Maris talks faded as McGwire hit only 14 home runs in the second half. Unfortunately, McGwire was also felled by a rib cage injury, causing him to miss 20 games from August to September. It was an ominous sign of things to come.

Foot and back injuries severely stifled McGwire’s progress over the next two seasons. He appeared in only 27 games in 1993 and 47 games in 1994. There were whispers that the newly developed muscles of his upper torso had grown too large too fast for his legs and feet. Even Tony LaRussa, McGwire’s manager at Oakland for nine seasons, thought that McGwire “got too strong for his frame.” Some comeback. Turn off the Rocky music. Three years after his “Jacuzzi moment,” McGwire’s career was spiraling southward once again. Although he seemed to have it all together mentally and with his swing, he just couldn’t stay healthy.

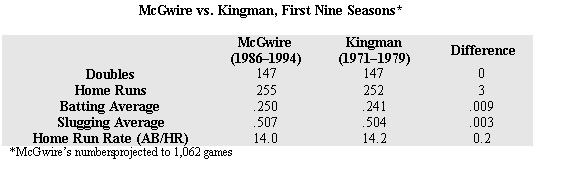

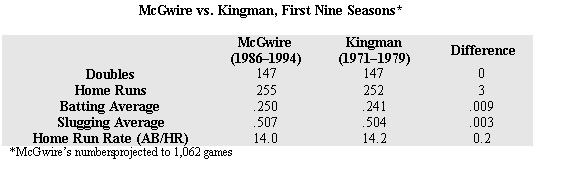

Going into the 1995 season, the 31-year-old McGwire was heading into his 10th major league season. It’s a good checkpoint on his career, considering that baseball history is filled with stars, even Hall of Famers, who were done producing by that age. With all that McGwire would eventually accomplish, it’s not a flattering comparison to look at the numbers he’d put up so far and see Dave “Kong” Kingman, another king of the tape-measure shot. Nine years into each of their respective careers, McGwire and Kingman had much more in common than just being USC alums. Some of the stats these two put up were almost clone-like. Projecting McGwire’s statistics of his first nine years upward to Kingman’s total of 1,062 games (McGwire had played 72 fewer games at that point), the numbers would fall like this:

Their batting and slugging percentages were separated by mere percentage points. Their home run rates were practically identical. Scaled to a typical 550 at-bat season, McGwire edged Kingman by just half a home run, 39.3 to 38.7.

Like McGwire, Kingman’s power binges often teased fans into thinking that one day he would challenge the Maris record. With his gangly 6’6″, 210-lb. frame, Kingman stood like a praying mantis in the box. Once he took his hack, Kingman’s large, looping uppercut was designed for one thing: sending the baseball as far away as possible, preferably to another planet. Sometimes his blasts did reach a different zip code. But Kingman was about as one-dimensional as a shoehorn. His home runs and strikeouts were plentiful, while everything else—such as singles, doubles, walks, and even moments of clubhouse cheer—were few and far between. On offense, he was either trotting around the bases after a four-bagger or walking back to the dugout after strike three. On defense, his glove might as well have been an oven mitt. And his difficulty as a teammate was considered so detrimental that he was once shipped out of town by four different teams in one year. Aside from Jose Canseco’s 462 career home runs, Kingman’s 442 bombs were the most ever by someone who was never seriously considered for the Hall of Fame.

Big Mac had a little more going on than Kingman. McGwire’s defense at first base was good enough to earn him a Gold Glove in 1990. He was willing to take a walk, which gave him much more value from an offensive standpoint. But in terms of power, McGwire was Dave Kingman during the first nine years of their respective careers.

Then at 31 years old, Big Mac drove off Kingman Lane and down a fork in the road toward a small town called Legendville.

In 1995 McGwire somehow hit a season’s worth of home runs and RBIs—39 and 90—in just 104 games, a little more than half a season of playing time. Despite a beaning that kept him out for a week plus a couple of visits to the disabled list because of back issues, McGwire put up an eye-opening AB/HR ratio of 8.1—far better than he had ever done before. Bob Alejo, McGwire’s off-season conditioning coach who prepared him for the ’95 season, chalked up the big guy’s new power efficiency to a matter of getting his legs in better shape to handle the added muscle mass he put on after his miserable ’91 season.

Previously, whenever McGwire went on a Maris-threatening streak like he did during the ’87 and ’92 seasons, he cooled off well before reaching any serious stage of the record chase. McGwire never really threatened Maris in ’95, but he put up numbers that started fans and statisticians cranking on their calculators, trying to project what was humanly possible for the big redhead if he could just stay on the field.

McGwire missed Oakland’s first 18 games of the 1996 season with yet another foot injury, but he made up for it big time. Amazingly, he reached 38 home runs by the end of July, once again on target for immortality. He came up short again, but continued to hit homers at an unearthly pace. With 52 home runs in just 423 at-bats that season, McGwire matched the ridiculous home run rate of the previous year, 8.1. It was clear that he was no longer just on a hot streak—he was now this good all the time. Fans pleaded for Big Mac to get in 150 games just to see what type of damage he could do. Strat-O-Matic nuts couldn’t wait for his card to arrive in the mail.

Like the Amazing Colossal Man, McGwire also grew physically larger before our very eyes—as vouched for by the changing sizes of his jersey, going from a size 44 in his minor league days to a Hulk-like size 52. “Looking at McGwire in ’87, he was simply a skeleton compared to his physique today,” observed Ray Fosse, long-time member of the A’s organization.

McGwire was always able to hit long home runs, but by ’96, his greatest bombs were reaching unimaginable distances. “The strength is unbelievable. He’s hit balls where other guys need cabs to get to,” A’s manager Art Howe said that year. “Every town we go into it seems he hits the longest ball hit in that ballpark.” McGwire-mania was gathering steam. His batting practice sessions suddenly became must-see events. Nobody, not fans, teammates, or opponents, would dare turn the other way when he was in the cage, because they truly believed there was a chance they could miss the longest home run they would ever see in their lives.

Continuing his date with destiny, McGwire conjured Maris’ ghost once again in 1997, hitting 24 home runs in his first 61 games. This time he came within sniffing distance of Maris. Knowing that his expiring contract and enormously growing stature in the game would demand a salary far out of range for Oakland’s traditionally thrifty ways, the A’s traded McGwire mid-season to the St. Louis Cardinals. His 58 total home runs between the A’s and the Cards fell just three short of the record, the closest anyone has been since Maris set it in ’61.

McGwire’s much larger physical presence and unfathomable home run trajectories had fans convinced that beating Maris’ record was now just a matter of time. As long as he could stay healthy and put in a full season, most believed the odds were longer for McGwire not to eclipse Maris.

The 1998 season was that time. It was a year for the record books and the story books; for the historians and for the fans. The Maris record fell to McGwire and Sammy Sosa that year, as fans and sportswriters knighted the dynamic duo as saviors to a game still suffering from the emotionally crushing blows of the strike-aborted 1994 season. More love flowed through the baseball world that year than a steamy romance novel. Prominent sportswriter Mike Lupica was inspired enough to capture the season’s poetic moments in his book Summer of ’98: When Homers Flew, Records Fell, and Baseball Reclaimed America. Broadcaster and former player Tim McCarver didn’t waste any superlatives in his own gush book, The Perfect Season: Why 1998 Was Baseball’s Greatest Year.

Not only did McGwire smash Maris’ magical 61 by hitting 70 that year, he was turning ballparks into his own video arcade. He swatted 135 home runs over the ’98 and ’99 seasons, a two-year stretch that leapfrogged Ruth’s (and baseball’s) best of 114 home runs over the ’27 and ’28 seasons. By the end of the decade, it was impossible to over-exaggerate the impact Mark McGwire had in the baseball universe. He was legendary, prolific, and completely dominant. What is especially stunning is that McGwire was already a premier long-baller prior to his transformation, yet he still blew those numbers away.

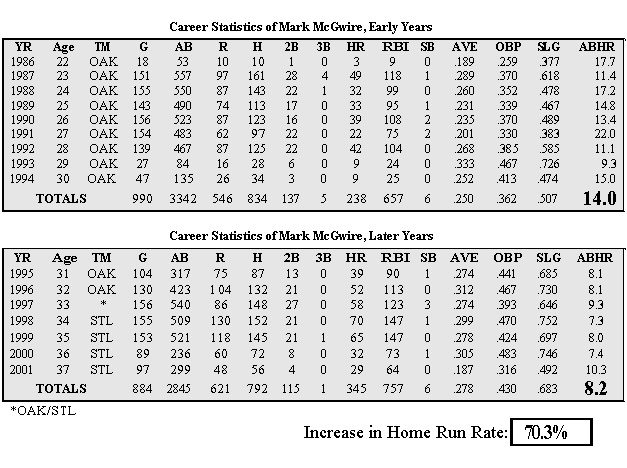

From 1995 to 2001, the last seven years of his career, McGwire almost doubled his own home run rate as he blew past the mighty Ruth. Over that time, McGwire averaged 49 home runs a year, sending baseballs over the fence at an unprecedented rate of once every 8.2 at-bats. Not only was this crazy seven-year pace 9% faster than Babe Ruth’s best season—when he hit 60 home runs in 1927—it was 70% faster than McGwire himself for the first nine seasons of his career!

At the end of the 2001 season, McGwire’s reign of greatness and glory reached an abrupt end. Knee problems forced him to retire, just two years removed from a 65-homer season. At that time, McGwire was considered first ballot material for the Hall of Fame by most fans and baseball experts, with his 583 career home runs ranking fifth all time behind Hank Aaron, Ruth, Willie Mays, and Frank Robinson. It’s hard to imagine that Babe Ruth was any more revered in his day than Mark McGwire was at the turn of the 21st century.

McGwire’s reservations for immortality were canceled four years later on a May afternoon in 2005. While facing a room full of probing politicians urging baseball to get its act together against steroids, McGwire transformed again—this time from epic baseball hero to speechless pariah—because he chose not to answer what was fundamentally a very simple question: “Did you take steroids?”

McGwire’s refusal to “talk about the past” with a direct answer was symbolic of an entire generation of ballplayers muted by their desire to keep their secrets hidden. Unfortunately for McGwire, the spotlight was extra bright that day, and he had nowhere to hide. To the media and to the fans, McGwire’s silence was so implicating, he might as well have had a syringe sticking out of his back pocket.

Not too long ago, Babe Ruth’s frequency of parking balls in the seats was at least 20% faster than anyone else, and it was that way for almost 80 years. Today, Mark McGwire ranks as the fastest home run hitter who ever lived. Unfortunately, now that he has admitted using steroids, Big Mac’s career AB/HR mark of 10.6 is a line in the record book that might as well have been written in invisible ink.

***

Jacuzzi® is a registered trademark of Jacuzzi, Inc.

THE SOURCES

- www.baseball-reference.com

- www.retrosheet.org

- Callahan, Tom and Lawrence Mondi. “It’s A Routine…Home Run,” TIME.com, July 13, 1987

- Wilstein, Steve. “McGwire Bulks Up With ‘Andro’: Testosterone Builder Isn’t Illegal In Baseball,” Rocky Mountain News, August 22, 1998

- “McGwire responds to muscle drug story,” Associated Press, August 23, 1998

- Nightengale, Bob. “Big Mac retires on his terms,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 21, 2001

- Kurkjian, Tim. “A’s O.k.: If you counted the Oakland Athletics out, count again. They’re flying high once more,” Sports Illustrated, April 27, 1992

- Murphy, Austin. “In Sight: Mark McGwire of the A’s could smash the game’s most storied record, Maris’s 61 homers,” Sports Illustrated, August 26, 1996

- Kroichick, Ron. “A.L. “West: Oakland Athletics,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1995

- Wulf, Steve. “Most Happy Fella: Oakland’s Mark McGwire is smiling again, now that he’s hitting homers at a record pace,” Sports Illustrated, June 1, 1992

- Anderson, Dave. “Comfy (Dave Kingman),” The New York Times (as appeared in Pacific Stars and Stripes), March 28, 1978

- Boyle, Robert H. “Scorecard: Figuring Sky King,” Sports Illustrated, December 12, 1977

- Pastier, John. “The Myth of the 500-Foot Home Run,” Slate Magazine, October 4, 1997

- Lang, Jack. “Sky King’s Dive Lets Air From Met Balloon,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1976

- Barrett, Ted. “McGwire mum on steroids in hearing: Sosa, Palmeiro deny use in front of House panel,” CNN.com, March 17, 2005