If Sammy Sosa were a NASA rocket ship, the launch date for his journey into the stratosphere of legendary power hitting would have been on May 25, 1998.

At the time, the Mark McGwire Missile was already soaring up ahead, with the St. Louis Cardinal having just hit his 25th home run in the 49th Cardinal game. McGwire’s 433-foot projectile put him on a senseless pace of 83 homers and 202 RBIs for the year, as the entire baseball world braced itself for the anointment of a new single season home run king.

Going into his game in Atlanta that evening, Sosa’s nine homers were light-years behind Big Mac’s 25. But after a solo shot in the top of the fourth followed by a three-run bomb in the eighth, Rocket Sosa left planet Earth. That night marked the beginning of the most explosive month-long home run binge in baseball history. Out of the 26 games Sosa played between May 25th and June 25th, he smashed a ridiculous 23 home runs in just 109 at-bats, a clip of one homer every 4.7 at-bats. Projected to 600 at-bats, his numbers read like the stats of a twelve-year-old boy playing Nerf down in his basement: 127 home runs, 248 RBIs, and a .972 slugging percentage.

Sosa’s twenty homers for the month of June gave him the major league record for most in any month. By the time the June 25th games hit the books, Sosa’s 32 home runs were just three behind McGwire’s 35. Away the two went, on a journey where no pair of sluggers had ever gone before. By mid-summer, the undisciplined, underachieving, and often criticized version of Sammy Sosa had been replaced by a hugely popular, muscle-laden superman who could hit a baseball over a tall building with a single swing of his mighty bat. By the year’s end, Sosa and McGwire became the dynamic duo who saved baseball, soaring past Roger Maris’ 37-year-old single-season home run record like it was some Dead Ball Era statistic. For Sammy Sosa, his 66-homer 1998 season was the year his career transformed.

Eleven years later, when his positive steroid test of 2003 was disclosed by the New York Times, Rocket Sosa splashed down into the acrimonious Sea of Disgrace. All efforts to recover his integrity were immediately aborted—his reputation was no longer salvageable. The news flash that steroids were found in Sammy Sosa’s system was as anticlimactic as the second pitch of a major league All-Star game. And not because of the big guns who had fallen to similar depths months earlier, namely Alex Rodriguez and Manny Ramirez. With Sammy, his reported drug test seemed to tie everything together—like locating the final clue to a long-unsolved mystery.

The skinny days

Putting a historical perspective on what Sammy Sosa has meant to major league baseball is a stickler, which is only fitting, because he’s been an enigma since the day Texas Ranger scout Omar Minaya scooped him out of the Dominican Republic as a 16-year-old. Sammy was as raw as they came, having played organized baseball for only a couple of years before being signed by the Rangers. He was so skinny, scouts thought he looked malnourished – hard to believe Rick Reilly of Sports Illustrated would one day label him a “bulky, 230-pound Mr. Olympus.”

Young Sosa’s game overflowed with talent and aggressiveness but was void of fundamentals or discipline. From a scouting viewpoint, the Sosa glass was seen as “half full,” despite the crudeness in his skills. With a strong and accurate throwing arm, a fast bat, and an energetic style of play, Sosa had a promising five-tool future. But Sammy’s ‘110%’ often ran too hot, like the pinned RPMs of a smoking, overheated engine. He had a habit of repeating the same mistakes in the outfield, on the base paths, and at the plate. He was stubborn and considered uncoachable by those who tried to tame his wild approach.

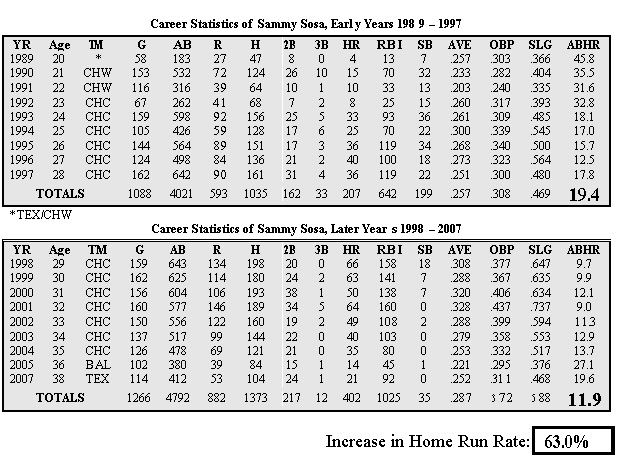

After nurturing Sosa in their farm system for four years, Texas gave up on him after only 25 major league games and shipped him to the Chicago White Sox. Sosa may have had enough talent for two ballplayers, but that promise was effectively negated because of his inability to either get on base or put the ball in play. Sammy continued to be an ongoing project with the White Sox. His lack of maturity in his skills and mindset at the big league level frequently came at a severe cost to his team. Over his first three big league seasons, he was caught stealing in 34% of his attempts. His strike out rate was that of an elite power hitter, yet his home run rate didn’t even come close. His awful on-base percentage (OBP) of .273 was proof of his unwillingness to work a count, wait for a good pitch, or draw a walk. As one coach put it, Sosa “never saw a pitch he didn’t like.”

Less than three years after getting Sosa from the Rangers, the White Sox grew frustrated by his refusal to lend an ear to hitting coach legend Walt Hriniak. A poor .227 batting average in 947 at-bats with the Sox sent Sosa packing again, this time just ten miles north to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for outfielder George Bell. Ironically, Sosa wasn’t even thought of as adding any power value to the Cubs lineup at the time. The Sporting News bashed the trade because they believed that letting Bell go “robbed the Cubs of needed thump in the middle of the order”—without an inkling that the Cubs were getting a man who years later would become arguably the most popular power slugger in the game.

But who could blame them? Sosa was still a good 30 to 40 pounds under the muscular frame he eventually carried during his Herculean record-breaking years later on, and at the time had just 29 career home runs in two seasons’ worth of at-bats.

The first bump to stardom

Sosa stuttered in ’92 with injuries. But the next year he started firing on all cylinders for the first time in his career. He finally approached the potential so many had waited patiently—and some not so patiently—for since the ’80s. Sosa put himself on the map as one of the best all-around talents in the game, becoming baseball’s newest 30/30 club member with career highs in home runs (33) and stolen bases (36). Although it seemed like it had been a long time since he was first signed, he was still only 24 years old.

Over the next four seasons, Sosa continued to combine power and speed like few others, averaging 34 homers and 26 stolen bases from ’93 to ’97. But there were those critics who still believed Sosa was an underachiever, which was as much a nod to his huge talent as it was a knock to his game. He struck out way too much, and his low IQ on the base paths continued to pile up the missed scoring opportunities. He was still an out maker, with much of his speed wasted chasing pitchers’ pitches. His selfishness in his own statistics, specifically the home runs and stolen bases, alienated teammates. Many of those same players grew weary of his “act” around the clubhouse, which had to do with Sammy Sosa’s wants and needs being stuck in the center of the Chicago Cub universe.

When the Cubs rewarded Sosa with a $42.5 million contract extension midway through the 1997 season, the team was heavily criticized for investing so much in a product that was still flawed in the eyes of many experts. Cubs general manager Ed Lynch explained, “We were banking that he would continue to improve.” From a production standpoint, Lynch’s return on investment from Sosa was like winning the lottery. Sosa’s blossoming into a star in ’93 was just a whisper of what was to come.

A career transformed

What Sosa did in 1998 took his game to a completely different level. In one season, he became a home-run-hitting powerhouse no longer of mortal resemblance, at least by historical baseball standards. There was no frame of reference…except for what Mark McGwire was doing 300 miles away in St. Louis. Fueled by his record-breaking month of June, Sosa joined McGwire in smashing the Maris record. Sosa led the Cubs to the playoffs with 66 home runs, 158 RBIs, 134 runs, and a .308 batting average, earning him the league MVP.

Over the five-year span following his grand transformation, Slammin’ Sammy averaged 58 home runs a season, a 71% increase from his previous five years. Only two times had anyone ever hit 60 or more home runs in a season prior to 1998 – once by Ruth and once by Maris. Sammy did it three times in four years. His new home run rate allowed him to leap-frog home run milestones with the ease of his two-finger salute. After hitting his 300th home run on June 26, 1999, it took Sosa just 23 months to hit his 400th, and another 23 months to hit his 500th. That’s 200 home runs in just under four years, a feat that may have triggered Reggie Jackson, owner of 563 career home runs, to voice his skepticism. “Somebody definitely is guilty of taking steroids,” Jackson complained to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2004. “You can’t be breaking records hitting 200 home runs in three or four seasons. The greatest hitters in the history of the game didn’t do that.”

To say that Sammy finally reached his potential in 1998 is grossly inappropriate. No one had him tagged for hitting that many home runs. Sosa’s potential was always about becoming a five-tool star. But that’s not what happened. As Sosa’s muscular build grew and his tape-measure home runs started landing more frequently in the 450- to 500-foot range, his speed gradually faded away. His five tools eventually dwindled down to two: hit, and hit with a ton of power.

But how?

As Sosa was putting up those frightening numbers throughout the ’98 season, many tried to rationalize why he started doing this type of damage at 29 years old. There was a common thread to the explanations from those who had witnessed Sosa try desperately over the years to overcome a slew of self-defeating habits at the plate.

“He doesn’t chase pitches the way he used to,” said Phillies manager Terry Francona. “The key has been his patience,” explained Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci. “There was no need to ever throw Sammy Sosa a strike. Now he’s making pitchers throw him strikes, and when he gets pitches he’s not missing them.” Even Sammy agreed. “The [bad] pitches that they throw me now that I used to swing at last year, I’m now taking them.”

Makes sense, right? With a better sense of the strike zone, most of those back-straining whiffs he took at breaking balls halfway up the first-base line vanished, giving Sammy more opportunities to swing at balls friendlier to his power stroke.

Except Sosa’s numbers show there was much, much more.

Sosa’s ’98 season was obviously a drastic improvement from the previous year. His home runs went from 36 to 66, his hits from 161 to 198, and his batting average from .251 to .308. However, though his walks did increase from 45 to 73, supporting the notion that he had become more patient at the plate, his contact rate both years was practically identical. Sammy was still the free-swinger.

Let’s suppose Sosa was being more patient in ’98 and leaving those tempting pitches off the plate. One might have expected him to make better contact because, on the whole, he would be swinging at a much better selection of pitches.

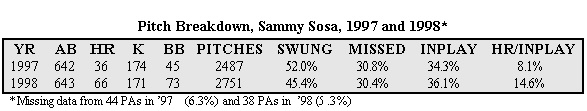

But this wasn’t the case. Check out Sosa’s pitch-by-pitch breakdown differences between the ’97 and ’98 seasons:

Not only was his frequency of striking out nearly identical in both years (1997: 174 Ks in 642 ABs, 1998: 171 Ks in 643 ABs), the percentage of balls he missed every time he swung was nearly identical (30.8% to 30.4%).

But the most compelling statistic for Sosa in 1998 – aside from the 66 home runs – was his improvement in the percentage of home runs he hit out of the number of balls he put in play. This number rose from 8.1% in ’97 to 14.6% in ’98, an 80% rise that stands tall as Sammy’s smoking gun. From his pitch-by-pitch breakdown stats, the cause behind Sosa’s home run rate almost doubling from ’97 to ‘98 was most likely due to an increase in strength that caused his fly balls to carry greater distances. Perhaps Sammy laid off more pitches than usual; but it was his ‘new’ strength that made him a more dangerous hitter. Even his large jump in hits shows evidence that his ground balls ripped through the infield much harder.

Let’s give the pitchers some credit. With the ’98 Sammy capable of hitting the outside pitch out of most ballparks (whereas in previous years he didn’t have that kind of power and would futilely try to pull that pitch), he became a new kind of danger for pitchers – and they reacted accordingly. The increase in walks was as much a result of a pitchers’ fear as it was Sosa’s improved pitch selection, if not more so. Perhaps those pitches away from the plate that were too enticing for free-swinging Sammy in previous seasons were going even farther away from the plate because of the intimidation factor, making Sammy’s decision process easier.

The transformed Sosa reached first base much more frequently. His OBP of .372 from 1998 through the rest of his career was 64 points higher than from his younger years. But remember, hits matter as much as walks when calculating OBP. Sosa’s average for the five years following his transformation was .306, a giant leap from the five years before, when it was just .268. In fact, while he was hitting 66, 63, 50, 64, and 49 home runs over five consecutive seasons, Sosa struck out more often (161 Ks per 600 ABs) compared to the five years before his transformation (147 Ks per 600 ABs).

Mr. Sammy Sosa, a disciplined hitter? Wrong answer. It was a freakish change in strength that powered Sosa starting in 1998.

The fall

Seven years after the Great Maris Home Run Chase of 1998, Sosa and McGwire embarrassed their sport, cowering in front of Congress at a time when the world was begging for someone—anyone—to own up to the disgrace of steroids. Sosa delivered an official denial in a prepared statement through his lawyers, but mysteriously suffered a memory lapse of the English language when it came to responding with his own voice. To many, his biz-suit performance that day was a dead give-away of how he did what he did.

The report of Sosa’s positive test result four years later was the clincher. The integrity of his career now hangs from the gallows of drug testing. Suddenly it’s really easy to forget the positive vibes that Sammy Sosa gave to the game of baseball. If you were a baseball fan in the late ‘90s, chances are you loved Sammy Sosa. His “let’s get this inning started” sprint to right field, his effervescent “I love baseball” smile, and the victory hop out of the box when he knew he just went yard—those were just a few of the reasons fans across the nation embraced Sosa. From spirit alone, he was good for the game. He showed Mark McGwire how to enjoy their dueling conquest of the Maris record, which made the entire chase in ‘98 an intimate affair between Sosa, McGwire, the Maris family, and all the fans watching at home. Sosa and McGwire transcended their sport that year, sharing “Sportsmen of the Year” awards from both Sports Illustrated and the Sporting News.

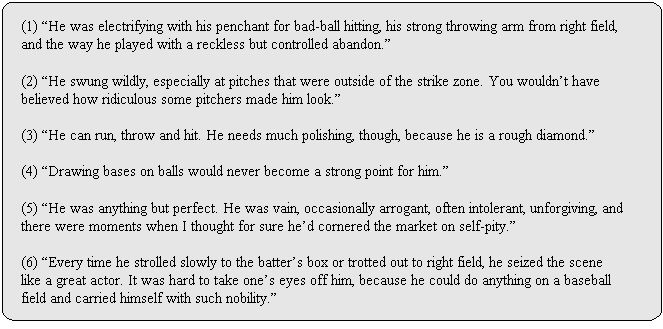

Before getting too far in the verbal and literary stoning of Sammy Sosa for his sins of steroid use, consider these quotes*:

These words sound like a perfect summary of Sammy Sosa’s career. But they were spoken about another slugging right-fielder with a great arm who, like Sosa, had a prideful hunger to be the best: Roberto Clemente.

Clemente was the idol of countless Latin American prospects who had a dream of leaving their country to play in the major leagues. Sammy Sosa took his worship of Clemente to the extreme, and not just by sharing the number 21 on the back of his Cub uniform. Sosa chased pitches to a fault, almost in honor of Clemente’s bad-ball-hitting reputation, which won Roberto four batting titles and a career batting average of .317. Sosa’s overzealous efforts are right in line with Clemente’s electric style of hustle that every dad would want his son to copy, on defense and on the base paths.

But it’s the pride aspect most of all that ties Sosa to Clemente. “Sammy probably had more pride than anybody I’ve ever been around,” said former Cub hitting coach Jeff Pentland. “Bonds is close, but Sammy was something else.”

Bonds. Sosa. Intense pride. Steroids. There just might be a connection.

Both Clemente and Sosa exhibited so much passion for their native country that they burned with the desire to represent their people and become the best they could be, any way they could. But how far would they go? Well, we’ve seen how far Sammy would go.

Shortly after Alex Rodriguez admitted that he injected himself with steroids, Mike Schmidt admitted that he “most likely” would have used steroids during his playing days if they had been available. He recognized how steroids became such an ingrained part of the game’s “culture” that he would have been tempted just like any of these other ballplayers. Several other retired players have similarly hinted that if steroids had been available and what they needed to get an edge, so be it.

What would Clemente, Sosa’s hero, have done? Vastly underrated for practically his entire career, Clemente spent years vainly trying to drum up the recognition he deserved. It took an all-around spectacular World Series in 1971 at age 37 for the national scene to finally awake to his extraordinary career accomplishments.

If steroids had been around and readily available in 1965 like they were in 1995, no one can say for sure that players like Clemente wouldn’t have indulged. They had the same desire to be the best, as did players from any other generation.

These are not bad people we’re talking about, just bad choices. Fortunately for Clemente, he didn’t have to make that choice. Sammy Sosa did.

– JDC

THE SOURCES

*All Roberto Clemente quotes were referenced from author and SABR member Stew Thornley’s biography of Clemente at SABR’s Baseball Biography Project (bioproj.sabr.org). In order, the quotes were spoken by: 1–Thornley; 2–Minor league manager Max Macon; 3–Legendary baseball executive Branch Rickey; 4–Thornley; 5–Reporter Phil Musick; 6– Pulitzer Price-winning journalist and author David Maraniss, author of Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, Simon and Schuster, 2006.

Additional sources:

- www.baseball-reference.com

- www.retrosheet.org

- www.baseball-almanac.com

- Adamek, Steve. Cubs’ Sosa emerging into genuine star, The Record (Bergen County, NJ), August 8, 1996

- Associated Press. Slugger doesn’t believe today’s athletes, ESPN.com, March 10, 2004

- Cubs’ Sosa on verge of stardom, Post-Tribune (IN), May 21, 1993

- Ginnetti, Toni. From star to superstar – Cubs slugger Sosa taking his game to the next level, Chicago Sun-Times, June 21, 1998

- Goddard, Joe. ‘Mr. White Sox’ Goes to Texas, The Sporting News, August 7, 1989

- Holtzman, Jerome. Sosa’s No. 1 Need: Discipline at Plate, Chicago Tribune, March 22, 1998

- Kiley, Mike. Sosa: Cut me some slack – Says people expect too much from him, Chicago Sun-Times, August 13, 1997

- Mariotti, Jay. Our sluggin’ Sammy, Chicago Sun-Times, June 28, 1998

- Mariotti, Jay. The Cubs are on their way, Chicago Sun-Times, January 18, 1998

- McGwire hits 25th, breaks another record, Associated Press, May 26, 1998

- Mitchell, Fred. At the plate, Sosa’s been a man with a plan: Patience, Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1998

- Pascarelli, Peter. Replacing Mitchell is no Giant problem, The Sporting News, May 25, 1992

- Reilly, Rick. Excuse Me for Asking, SI.com, July 2, 2002

- Schmidt ‘Most Likely’ Would Have Used Steroids, youtube – MyFoxPhilly, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enGnm9NsxD0, February 2, 2009

- Schmidt, Michael S. Sosa is Said to Have Tested Positive in 2003, The New York Times, June 16, 2009

- Schulman, Henry. San Francisco Giants – Bonds is a team player when it comes to taking walks, The Sporting News, September 10, 2001

- Slammin’ Sammy: An Inside Look, Sports Illustrated (an interview between CNN/SI and Tom Verducci), June 23, 1998

- Sosa ejected after cork is found in shattered bat, ESPN.com, June 3, 2003

- Sosa is out 4-6 weeks – X-rays reveal hand fracture, Chicago Sun-Times, August 21, 1996

- Sullivan, Paul. New Attitude, Old Power From Sosa, Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1997

- Sullivan, Paul. Sosa has a record already 21 homers in 30 days tops Kiner, Maris, Chicago Tribune, June 24, 1998

- Van Dyck, Dave. Chicago Cubs – Fly on the wall, The Sporting News, April 13, 1992

- Van Schouwen, Daryl. 40-40 Not in Sosa’s Vision – Outfielder Keeps Mum on Goals, Chicago Sun-Times, April 1, 1996

- Verducci, Tom. Adios, Amigo – With his power gone and his dignity under assault, Sammy Sosa calls it quits, Sports Illustrated, February 27, 2006

- Verducci, Tom. The Education Of Sammy Sosa – Having learned that his personal goals and those of the team can be reached with a single stroke, the Cubs slugger produced the greatest home run streak the game has ever seen, Sports Illustrated, June 29, 1998