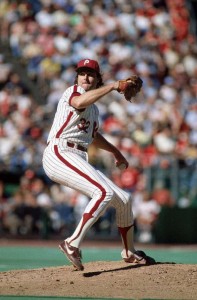

Until next season unfolds, Phillies fans are going to gripe that GM Ruben Amaro lost his mind sending Cliff Lee out of town just four and a half months after he acquired him in the genius transaction of the 2009 season.

But before getting too hung up on this “Cliff Lee or Roy Halladay” debate, remember that the Phils won the World Series in ’08 without either pitching stud. The guy we really should be paying attention to is that “other” starting pitcher, Cole Hamels.

After leading the Phils to the title as their undeniable ace, Hamels laid a stink bomb in ’09. His performance—a 10-11 record with a 4.32 ERA during the regular season followed by 16 earned runs in 19 post-season innings—wasn’t just a valley point…it was self-inflicted. His elbow started aching during spring training before he had a chance to get in shape, and he never got his ace material on track.

If Hamels even sniffs the high standard he set previously, maybe the Phils take the Yanks. So the real burning question for the Phillies in 2010 has to be, “Will Cole Hamels return to form?”

We’ve heard the stories about Cole being more of a party animal last winter than someone who was supposed to get his arsenal in gear for the coming season. “I pretty much didn’t fulfill my end of the bargain,” he admitted last April, “and get ready the way I should have.” If anything, he proved there’s no rest when it comes to sustaining success in the big leagues.

But Phillie fans should cross their fingers and hope that 2009 was his mulligan, because there’s a precedent in baseball for greatness being taken for granted, then suddenly disappearing forever. It’s happened over and over.

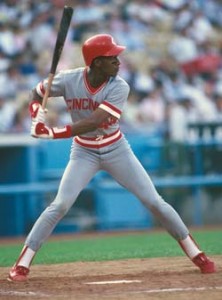

Sometimes it’s due to the fate of injury. Eric Davis was baseball’s next superstar of superstars in the late ’80s, capable of hitting the long ball (37 bombs in ’87), stealing bases (80! in ’86), and catching fly balls (Gold Gloves in 1987, ’88, and ’89) with the best in the game. But it all crumbled quickly for Davis with a string of misfortune that started with the lacerated kidney he suffered while diving for a ball in the 1990 World Series.

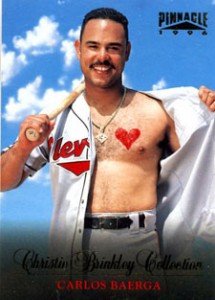

Sometimes a player dooms himself with the lifestyle choices he makes. One young star from the early ’90s had a future so bright, he was called “baseball’s best-kept secret.” After batting .312 with 205 hits and 20 home runs as a 23-year-old second baseman, the Sporting News said Carlos Baerga was “close to being baseball’s best player.”

The next year, Baerga followed up with a .321/200/21 season, causing Hall of Famer Joe Morgan to chirp how rare it was for such a talent to come along at the second base position. At the time, the only other second baseman to put up that combination of numbers in a season was Rogers Hornsby.

While experts had Baerga tagged as a future member of the 3,000-hit club, Indians GM John Hart shot up a warning flare, noting Baerga’s weight gain of 15 pounds. “I think Carlos is playing heavy right now,” Hart said. “He has the kind of body type that is going to make it difficult for him, unless he pays more attention to his conditioning.”

Unfortunately for Baerga and the Indians, Hart’s prophesy came true sooner than anyone could have imagined. The very next season, Baerga’s batting mechanics were shattered. The rocketing line drives off his bat turned into a smattering of pop-ups and weak groundouts. The Indians believed the 27-year-old Baerga, now a good 25 pounds overweight, lost it all—his desire, his skills, everything—and shipped him to the New York Mets.

Baerga’s career took an immediate dive into the sea of mediocrity, never to return to the promise of his early 20s. He played his last full season at 29 years old, and after touring the independent leagues trying to hook on to a major league roster, he played his last game at 36, one-thousand four-hundred and seventeen hits shy of 3,000.

According to ex-teammates and managers, Baerga fell too much in love with the celebrity of being a million-dollar athlete, becoming practically narcissistic in a whirlwind life of entourages, late-night bar hopping, and dancing the night away. “I think that, for whatever reason,” explained Indians manager Mike Hargrove, “Carlos just forgot how hard he had to work to become the player he was.”

It’s not like Hamels went Baerga on us last winter trying to live up to his “Hollywood” nickname. His ‘partying’ was more about the usual business that follows a world championship, with his time constantly beckoned with talk shows, commercial gigs, and mag shoots. He rarely said no.

But don’t hand him that comeback player of the year award just yet. If Cole were a consumer product, you’d definitely want to pay the extra bucks for the extended warranty. Not that he has a body structure that’s vulnerable to an early decline like the burgeoning Baerga. But with his fragile back, joints, and psyche, Hamels seems to require as much maintenance as a puddle jumper with 200,000 miles.

Can he dominate again? With age still on his side, I like his chances, but only if he learned from the most important lesson of his awful ’09 season: Talent can take a ballplayer only so far. It’s up to the athlete to sweat out the rest.